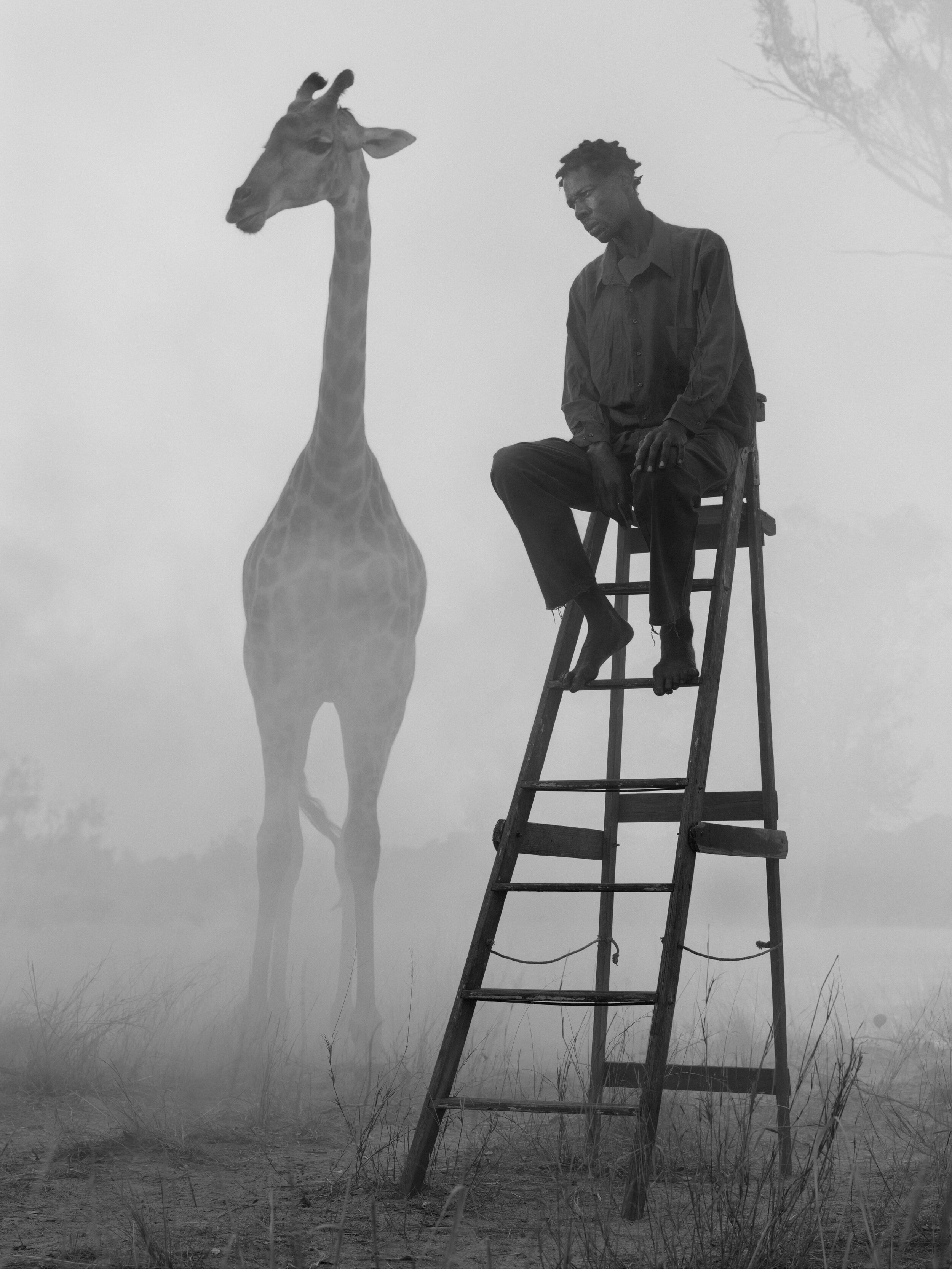

Nick Brandt - Halima, Abdul, and Frida, Kenya, 2020 - Courtesy WILLAS contemporary - Archival Pigment Print - Limited editions - Enquire

The Day May Break by Nick Brandt at Sliperiet

WILLAS contemporary is pleased to present Nick Brandt: The Day May Break, an exhibition of new works, photographed in Zimbabwe and Kenya in late 2020 and Bolivia in 2022. It is the first parts of a global series portraying people and animals that have been impacted by environmental degradation and destruction. The people in the photos have all been badly affected by climate change - some displaced by cyclones that destroyed their homes, others such as farmers displaced and impoverished by years-long severe droughts.

The photographs are taken at sanctuaries/ conservancies. The animals are almost all long-term rescues, victims of everything from the poaching of their parents to habitat destruction and poisoning. These animals can never be released back into the wild. As a result, they are habituated, and so it was safe for human strangers to be close to them, and photographed in the same frame at the same time.

The fog is the unifying visual. We increasingly find ourselves in a kind of limbo, a once-recognizable world now fading from view. Created by fog machines on location, this often renders the animals almost a dream, or a memory of what the people once experienced in their lives. It is also an echo of the suffocating smoke from the wildfires, driven by climate change, devastating so much of the planet.

However, in spite of their loss, these people and animals are the survivors. And therein lies possibility and hope.

Nick Brandt is an artist and witness who seizes bleak and desperate fates, and by some mystery and alchemy, transmutes these into a gesture of poignant and painful beauty.

It has been an eon, and then some, since I experienced contemporary photographs of people of African roots created by a person of Euro-American origin, that were this tender, human and gorgeous.

— Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, from the Foreword to The Day May Break, Author of Dust and The Dragonfly Sea.

Nick Brandt - Najin and people in fog, Kenya, 2020 Courtesy WILLAS contemporary - Archival Pigment Print - Limited editions - Enquire

A landmark body of work by one of photography’s great environmental champions. Showing how deeply our fates are intertwined, Brandt portrays people and animals together, causing us to reflect on the real-life consequences of climate change. Channelling his outrage into quiet determination, the result is a portrait of us all, at a critical moment in the Anthropocene.

— Phillip Prodger, Curator, Author, Photography historian, former Head of Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

The book The Day May Break (Hatje Cantz, 2021; 168 pages) and The Day May Break Chapter II (Hatje Cantz, 2023; 144 pages) - will be available for purchase at Sliperiet while supplies last.

A 5% percentage of artists’ and gallery’s share of the print sale proceeds will be evenly distributed on a biannual basis to each of the people photographed, as a kind of ongoing royalty payment. For a project about climate change, this production had better be carbon-neutral. It is.

Where: Sliperiet - Borgvik - Sweden

When: May 20th - August 27th 2023

Opening hours:

W.21-25 Thursday - Sunday 11.00-17.00

W.26-32 Every day 11.00-17.00

W.33-34 Thursday - Sunday 11.00-17.00

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

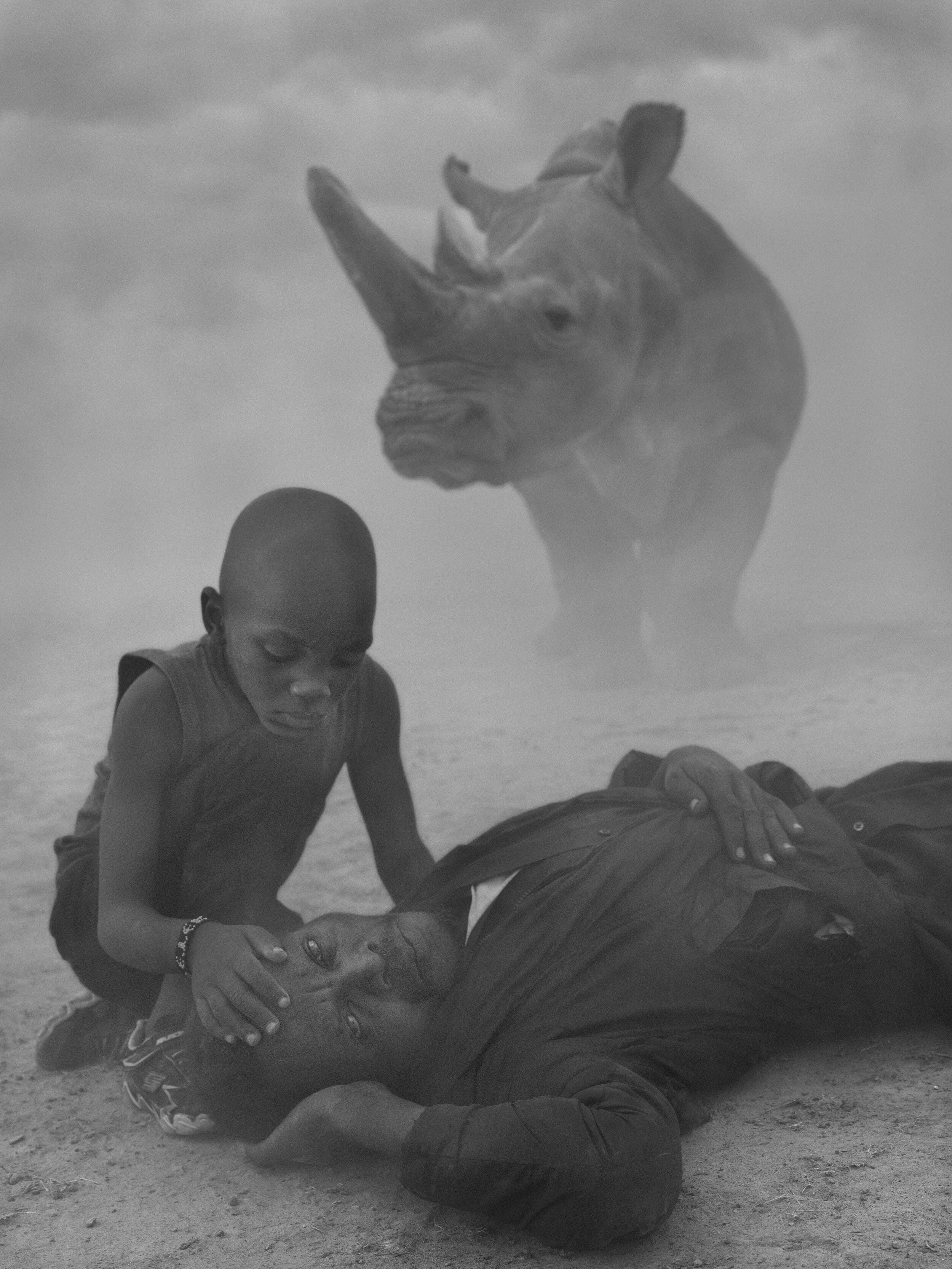

GITHUI AND NAJIN BY TREE, KENYA, 2020

Githui remembers the time when the climate never used to be this dry. But severe droughts forced him to abandon his farmland in central Kenya. With the death of his children, he moved to Nanyuki, where initially he was forced to take laborer jobs. Now he walks with difficulty and cannot find employment.

Najin is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. When her daughter, Fatu dies, the species will be extinct.

Once upon a time, the northern white rhino’s range extended through central Africa. But decades of poaching have taken its grim toll.

Najin and Fatu were both actually born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males in Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Najin and Fatu.

Photographed at Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya, October 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

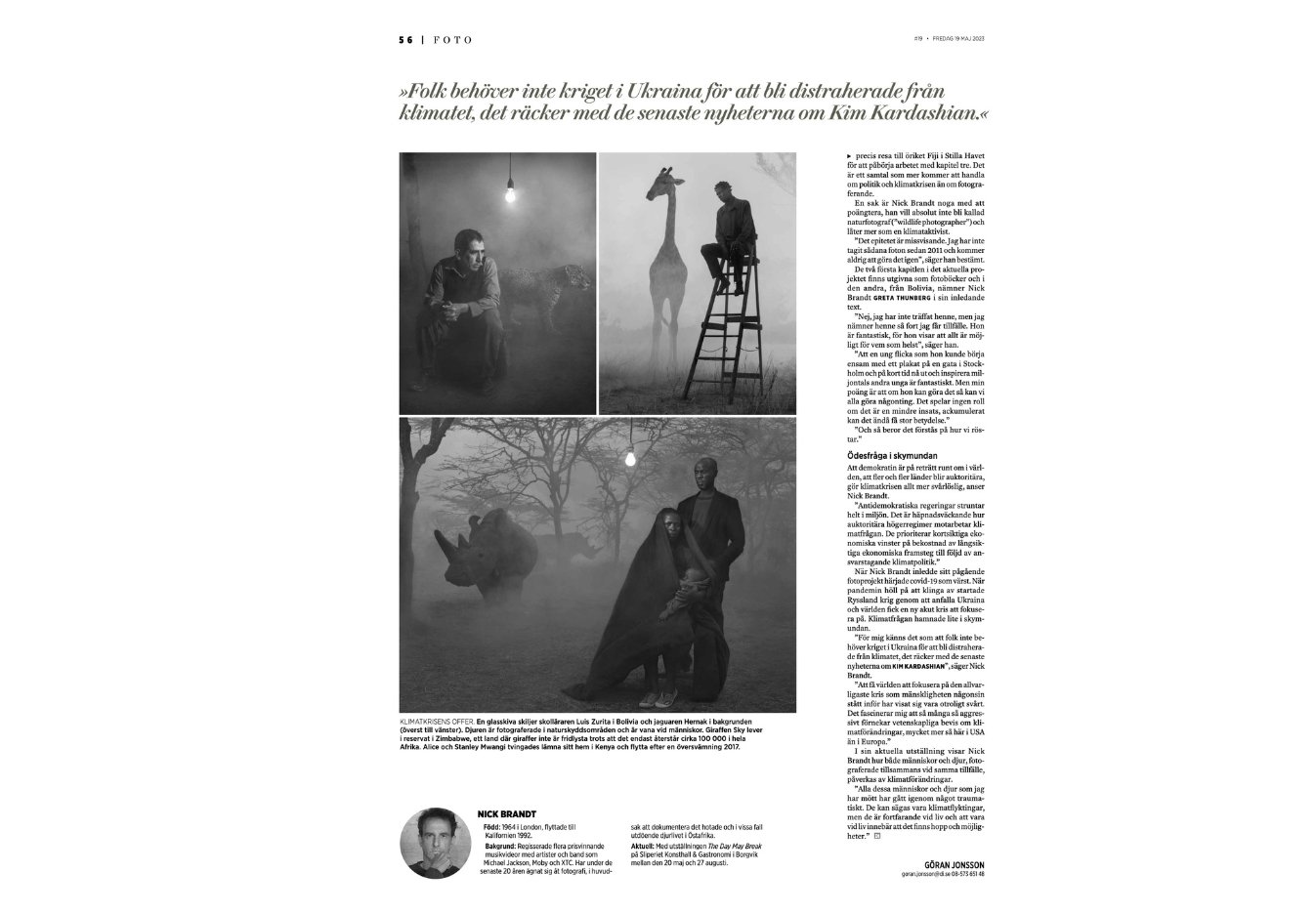

HELEN AND SKY, ZIMBABWE, NOVEMBER 2020

Helen has a small plot of land where she tries to farm maize, but because of the lack of rainfall and dried up wells, her crops have repeatedly died. In 2019, almost all her chickens also died because of disease. As a result, she has little food and lives in poverty.

Sky is four years old, a southern African giraffe. She came from a farm south of Harare.

The original wildlife there was nearly all killed by new settlers, leaving just two giraffes. Due to her age and perhaps also trauma, she had been unable to raise her own calves: when she had a calf, they always died because she did not feed them. The farmer called Wild Is Life to come and help. At the sanctuary, the calves Sky and Missy were raised until they were well enough to survive on their own.

The southern African giraffe, of which, as of 2021, there are less than 30,000 remaining in the wild, is listed as threatened. Across the whole continent of Africa, there are barely more than 100,000.

Shockingly, in Zimbabwe, giraffes are not a protected species; hunting, the removal of animals and animal products from a safari area, as well as the sale of animals and animal products is permitted.

Photographed at Wild is Life, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

KUDA AND SKY II, ZIMBABWE, 2020

It was March 31, 2019. The heavy rains and winds came unexpectedly. Kuda’s family didn’t own a radio to hear the news about Cyclone Idai, so they didn’t understand where exactly they were supposed to go to avoid it.

Kuda’s family lived in a low-lying area in eastern Zimbabwe, so they were the hardest hit. The floods and avalanches destroyed everything in the village. Kuda, her husband, and three children were all swept away. Kuda managed to swim and reach her home, but the cyclone had destroyed everything. Six months pregnant at the time, Kuda suffered a miscarriage. Two of her children were never found.

Currently, Kuda, her husband, and their one surviving child are living in a makeshift camp for displaced people affected by the cyclone. When interviewed about what happened to her, a year and a half after the cyclone, she said not to worry about her. She said that nowadays, “my life is like a ripened banana.”

Cyclone Idai was a terrifying harbinger of what climate change will bring in the coming years: more frequent high-intensity storms. And with that comes, of course, more destruction.

Sky is four years old, a southern African giraffe. She came from a farm south of Harare.

The original wildlife there was nearly all killed by new settlers, leaving just two giraffes. Due to her age and perhaps also trauma, she had been unable to raise her own calves: when she had a calf, they always died because she did not feed them. The farmer called Wild Is Life to come and help. At the sanctuary, the calves Sky and Missy were raised until they were well enough to survive on their own.

The southern African giraffe, of which, as of 2021, there are less than 30,000 remaining in the wild, is listed as threatened. Across the whole continent of Africa, there are barely more than 100,000.

Shockingly, in Zimbabwe, giraffes are not a protected species; hunting, the removal of animals and animal products from a safari area, as well as the sale of animals and animal products is permitted.

Photographed at Wild is Life, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

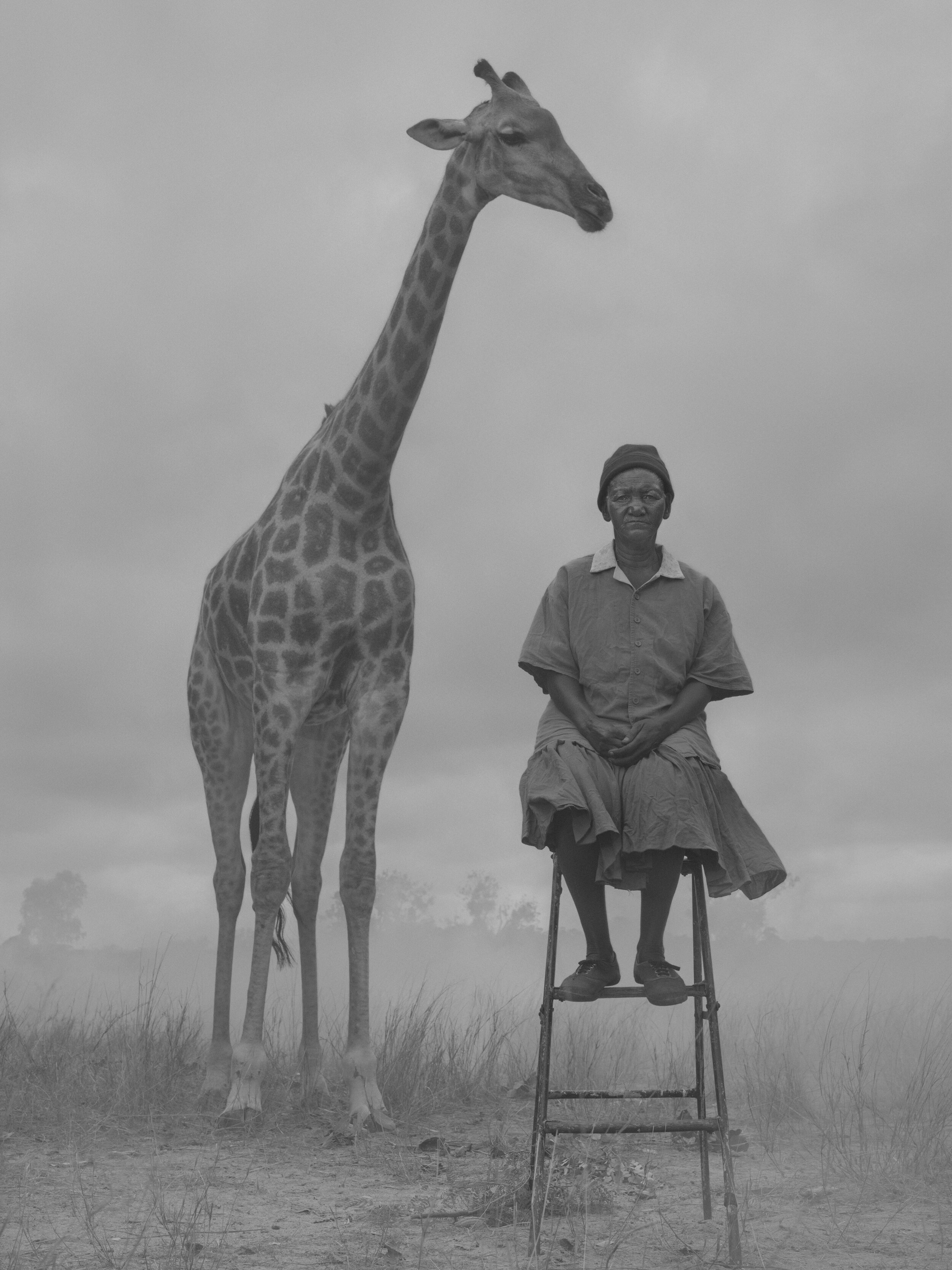

LUCKNESS, WINNIE AND KURA, ZIMBABAWE, 2020

Before Cyclone Idai hit, Luckness was employed and lived an uneventful life. But the cyclone destroyed her house, and she and her two children were swept away by the waters. One of her two children suffered a spinal fracture, which has left her permanently disabled.

Currently, Luckness and her children are living in a makeshift camp for displaced people affected by the cyclone.

Cyclone Idai was a terrifying harbinger of what climate change will bring in the coming years: more frequent high-intensity storms. And with that comes, of course, more destruction.

Kura was just three years old when he came to Wild Is Life (he was eight when photographed). He had been rejected by the Chinese for shipment of about 35 young elephants to China, and was one of three that Wild Is Life negotiated the release of. All of them had what was perceived as imperfections that resulted in their rejection: damaged or partially missing trunks, and in the case of Kura, a very badly broken leg, the cause of which is unknown.

The two other elephants were eventually able to move up to Wild Is Life’s Zimbabwe Elephant Nursery in a park in the north of the country, near Victoria Falls. But because Kura’s leg was so severely damaged, it was felt that he would not be able to manage the rough terrain at the release site, or cope with getting into a fight with another bull. If there is an easier release site, or a more sanctuary-type situation, he may go there.

Meanwhile, Kura is very gentle with all the younger rescued calves, and a great teacher to the young bulls.

Photographed at Wild is Life, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

MATTHEW AND MAK, ZIMBABWE, 2020

Matthew grew up near Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe. He says the place as beautiful when he was younger, but from around 2010, years of extended harsh drought have resulted in the forests drying out and crops failing. His livestock also died. It has become hard for him to afford to send his children to school.

Even wells are running dry, and with that, the need to walk further each month to find water. And as deforestation continues apace, animals are forced into areas of human occupation, destroying crops and coming into conflict with the farmers.

A century ago, there was an estimated 10 million elephants stretched across the length and breadth of sub-Saharan Africa. Today, in 2021, there are, at best, 400,000 remaining in the wild, mainly due to poaching for their ivory.

Zimbabwe has the second highest population in Africa, perhaps 65,000 as of 2020. However, since 1965, the country has engaged in the periodic culling of elephant herds, families, and individuals, due to what is regarded as an excess population.

Once upon a time, there would have been no such thing as an “excess population,” because there would have been enough land for them to roam and migrate. But with habitat loss and destruction, and human encroachment, this forces elephants into the remaining uninhabited areas, resulting in severely damaged woodlands from overgrazing. And then the culling begins.

With climate change, the situation becomes much worse, as vegetation and woodland dies off and burns, and humans and wild animals search for what remains.

And so we come to Mak. It was 1986. Elephants were being culled in Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe. Mak’s mother was one of those culled. Mak, a very young, and now traumatized calf, was rescued with three others. As he grew, he became too much for his carers. That was why he ended up at Imire when he was about five. (He was photographed here when about 35 years old). It took many years to gain his trust, but now once granted, it is there for life.

Into the future, the key is to create and conserve trans-African migratory corridors, to allow the elephants and other wildlife to migrate between countries.

Photographed at Imire Wildlife & Rhino Conservancy, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

THOMAS AND VINCENT, ZIMBABWE, 2020

Thomas and his wife Monica have been small-scale farmers in Zimbabwe for the past ten years. But for the last three years they’ve found it difficult to survive because of the extreme drought. Their well is now dry, so they have to walk 5km to fetch drinking water.

Thomas can operate a tractor with a ripper, but everyone is in the same situation: no one wants to gamble using a tractor to prepare the land if their crops fail from drought.

An anti-poaching unit found Vincent as a chick on the ground in the Bumi Hills conservancy area but could not find his nest. Vincent was young enough that he had just started to fly, so he was perhaps just starting to fly from the nest.

Hooded vultures are currently listed as critically endangered. Habitat degradation, persecution, and perhaps above all poisoning are the main problems. One recent example from Kuimba Shiri: in February 2020, a farmer poisoned the carcass of a cow in order to kill dogs (doubly horrifying). Out of a flock of 300, over 50 vultures died. Kuimba Shiri managed to rescue, rehabilitate, and release 21 of those.

Photographed at Kuimba Shiri Bird Sanctuary, Zimbabwe, December 2020

"

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

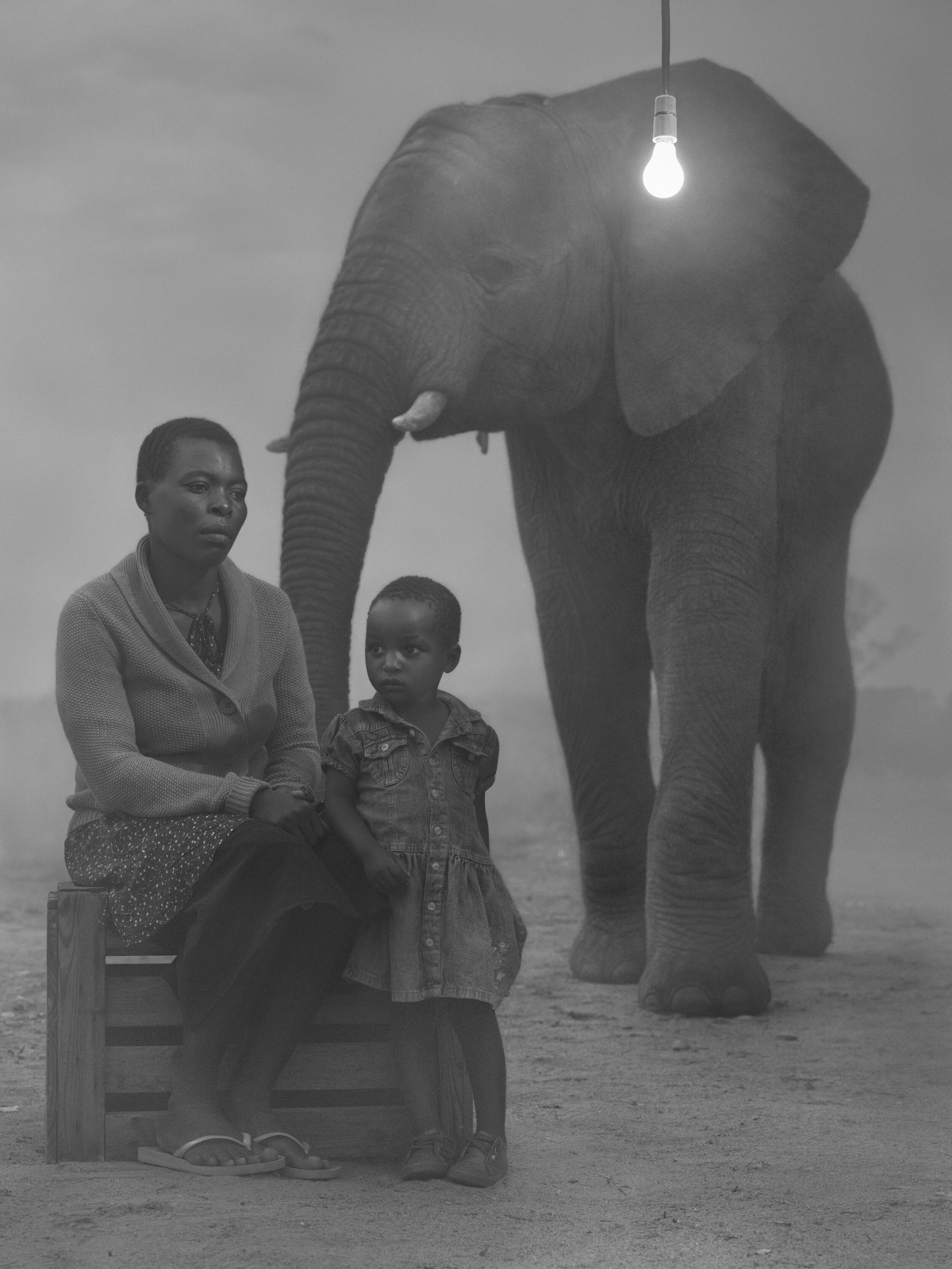

TERESA AND NAJIN, KENYA, 2020

Teresa and Samuel used to live and farm in the central highlands of Kenya. But in 2016, after three months of constant rain, landslides from the flooding destroyed their house and killed their livestock.

They were forced to move to Nanyuki, where life has been a huge struggle, hustling to find menial jobs. Samuel says: “I don’t even like to remember where we lived before. It’s too upsetting.”

Najin is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. When her daughter, Fatu dies, the species will be extinct.

Once upon a time, the northern white rhino’s range extended through central Africa. But decades of poaching have taken its grim toll.

Najin and Fatu were both actually born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males in Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Najin and Fatu.

Photographed at Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya, October 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

ZAINAB, HER MOTHER MIRIAM AND FRIDA, KENYA, 2020

Miriam was married and used to live near a river in central Kenya. Her house was destroyed in 2017 by the river bursting its banks during the floods, and she lost everything. Miriam wasn't there because she was visiting a relative, so her husband blamed her for the loss; he left her and daughters Zainab and Amina with nothing.

They all now live in a rented room in Nanyuki while Miriam sells fruit and vegetables.

In 2018, Frida, a greater kudu, was found when very young at the entrance gate of Ol Jogi. There is a high possibility that her mother was killed by some hunters, a victim of the illegal bushmeat trade.

Kudu are declining in population across areas of sub-Saharan Africa due to illegal bushmeat poaching, habitat loss, and deforestation.

Photographed at Ol Jogi Conservancy, Kenya, October 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

JAMES, PETER AND NAJIN, KENYA, 2020

James, here with his son Peter, used to own a 5 acre farm in central Kenya. He was successful and “life was good.” But years of long droughts made making a living harder and harder, until 2015, when bankrupt, he was forced to move and look for a job of any kind. This formerly proud, independent farmer has been reduced by climate change to being a casual laborer in the county market.

Najin is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. When her daughter, Fatu dies, the species will be extinct.

Once upon a time, the northern white rhino’s range extended through central Africa. But decades of poaching have taken its grim toll.

Najin and Fatu were both actually born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males in Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Najin and Fatu.

Photographed at Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya, October 2020

"

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

JAMES, PETER AND NAJIN, KENYA, 2020

James, here with his son Peter, used to own a 5 acre farm in central Kenya. He was successful and “life was good.” But years of long droughts made making a living harder and harder, until 2015, when bankrupt, he was forced to move and look for a job of any kind. This formerly proud, independent farmer has been reduced by climate change to being a casual laborer in the county market.

Najin is one of the last two northern white rhinos in the world. When her daughter, Fatu dies, the species will be extinct.

Once upon a time, the northern white rhino’s range extended through central Africa. But decades of poaching have taken its grim toll.

Najin and Fatu were both actually born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males in Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Najin and Fatu.

Photographed at Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya, October 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

REGINA, JACK, LEVI AND DIESEL, ZIMBABAWE, 2020

For Jack and Regina, their only source of food is a small plot of land for growing maize and vegetables. However, in recent years, their crops have failed, and with the worsening drought most of the local rivers and wells have dried up. This has forced them to go begging for water in surrounding areas. Sometimes they go for as long as a couple of months with little food, forced to live off handouts.

Diesel and Levi’s mother was killed by a farmer protecting his livestock. They came to Wild Is Life when they were about six weeks old, full of ringworm and very thin. Wild Is Life managed to pull them through, but because they were so young and so domesticated, it was decided that they were poor candidates for release.

They get taken for walks every day for enrichment. Fourteen years old when photographed, they have had healthy lives. In March 2021, Diesel died at age fifteen, a grand old age for a cheetah, whose average life span is 10-12 years.

The current situation for cheetahs in Africa is stark: driven out of over 90% of their historic range, the population across the continent is down to less than just 7,000 in 2021. At the current rate of decline, cheetahs are heading toward extinction.

As ever, habitat loss is one of the main reasons. With that also comes the decline and disappearance of the species that they prey on, as those in turn are killed by humans for bushmeat.

Photographed at Wild is Life, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Archival pigment print, Signed, Titled, Dated, Numbered Verso

Small 51 x 68 cm – Ed. of 15

Medium 71 x 94 cm - Ed. of 12

Large 102 x 135 cm – Ed. of 10

RICHARD AND SKY, ZIMBABWE, 2021

Richard lives with his wife and children in eastern Zimbabwe. Originally, a maize farmer and cattle owner, extended droughts from 2010 onward began to dramatically impact his livelihood. He drilled a borehole, but it has since run dry. So he turned to farming tobacco as a way to survive. Richard used to own fourteen cattle. But because of the drought, all the cows have died from disease. Richard now struggles to provide for his family and is unable to send his children to school.

Richard feels that the reduction in rainfall has been caused not just by climate change, but also by the clearing of forests for the production and curing of tobacco, which has left vast stretches of forests in the area barren.

Sky is four years old, a southern African giraffe. She came from a farm south of Harare.

The original wildlife there was nearly all killed by new settlers, leaving just two giraffes. Due to her age and perhaps also trauma, she had been unable to raise her own calves: when she had a calf, they always died because she did not feed them. The farmer called Wild Is Life to come and help. At the sanctuary, the calves Sky and Missy were raised until they were well enough to survive on their own.

The southern African giraffe, of which, as of 2021, there are less than 30,000 remaining in the wild, is listed as threatened. Across the whole continent of Africa, there are barely more than 100,000.

Shockingly, in Zimbabwe, giraffes are not a protected species; hunting, the removal of animals and animal products from a safari area, as well as the sale of animals and animal products is permitted.

Photographed at Wild is Life, Zimbabwe, November 2020

Nick Brandt: ´James-and-Fatu_Kenya, 2020´ - Courtesy WILLAS contemporary Archival Pigment Print - Limited editions - Inquire